After two decades of waiting, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) were finally approved and rolled out in China in 2021. For some it didn’t take long before getting into trouble.

REITs are designed to provide opportunities for people to invest in real estate projects without having to own an entire building or manage it. They tend to have large portfolios of office towers, shopping malls, logistic warehouses, or business parks under management, often in the billions of dollars. China was running trial runs with REITs since 2004 but it took almost two decades before they finally debuted on the stock market.

In recent weeks some REITs in China have come under investigation, accused of overpaying for assets and thereby defrauding their investors. How did the alleged fraud work?

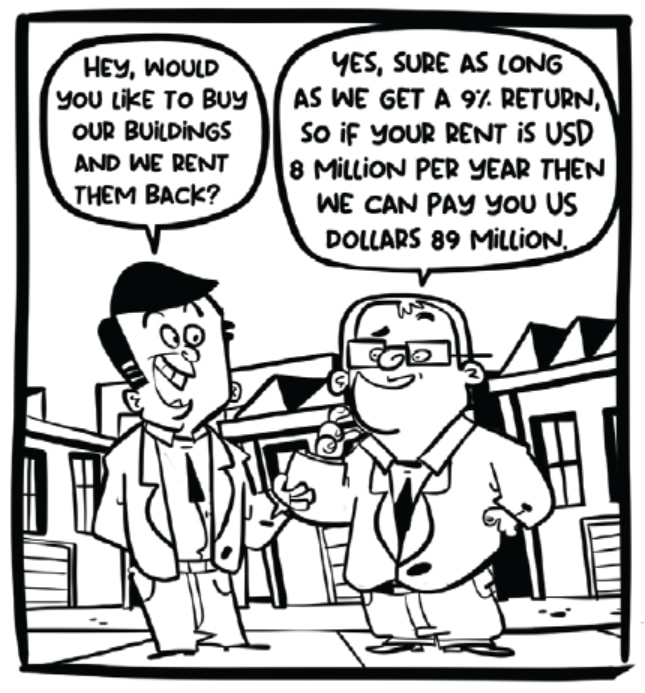

One scenario that has drawn investigator attention is where owner-users of buildings sell their properties to an investor, for example a REIT, and then rent them back. There’s nothing wrong with such sale-and-leaseback deals per se. They can actually be a great way for companies to convert a fixed asset into cash, especially when the company believes that it can create higher returns from the freed-up capital by investing it in their business.

A problem arises, though, when a seller wants to aggressively overprice their property and, as a way to convince the buyer to accept the deal, agrees to pay inflated rental rates. For example, a company may suggest to sell their buildings at twice the current market value and in order to get a buyer to agree to such an outrageous valuation the seller (=future tenant) may agree to also pay twice the going rental rate. Initially this may look fine in the buyer’s books, but problems easily arise.

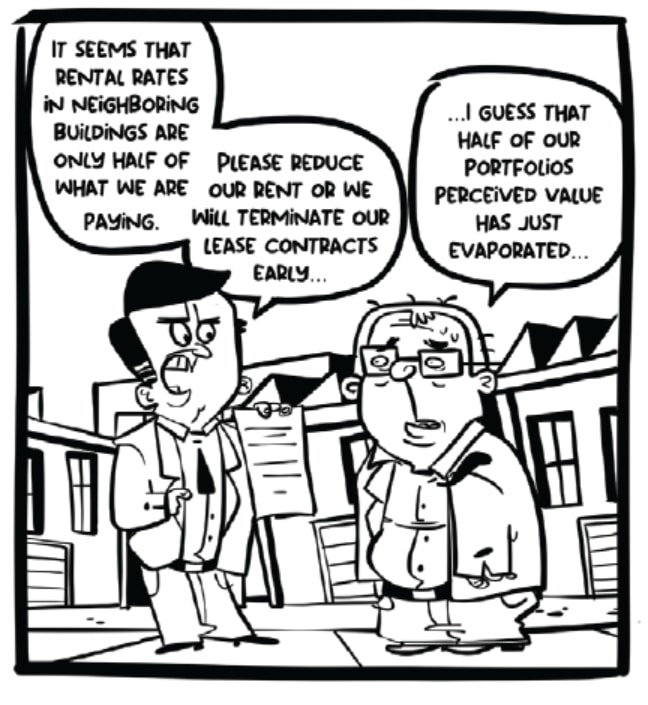

Currently there are a number of companies that underwent a process which may have looked a bit like the one described above. And now their businesses are facing pressure, perhaps due to the wider economic situation, but also because they are paying rents that are much higher than current market rates. They are now asking their REIT landlords for rent reductions and are referring to changed market conditions as explanation.

But real estate prices tend to be somewhat transparent, at least to government authorities who may be able to access construction contracts, lease contracts, tax statements etc. for almost every building in their jurisdiction. If industrial rental rates have declined by about 10% in a given market but a tenant demands a reduction of 50% then questions naturally arise. Why did the company initially agree to such a high rental rate? If they now want to drastically reduce the rent, will they also return some of the funds they received when they sold the buildings? If the new owner, e.g. REIT, agrees to accept lower rental rates, how can they explain that to their investors?

It seems to be a classic case of wanting to ‘have your cake and eat it too’. Maybe no regulator would have ever noticed the funny activities if market conditions hadn’t changed. Maybe those investing into such a REIT would only have noticed after about 5 to 7 years, once the buildings were being sold again, that the profit was less than expected. And maybe by that time values would have somewhat increased, absorbing some of the gap.

The scheme may have worked when sale-prices as well as rental-prices were inflated by a more modest 10 to 20% but, at least in the case that made biggest headlines in China, the overpricing was far more audacious. By aggressively overpricing assets and then calling for a change in terms the tenants have now exposed themselves and in addition exposed the REITs.

Naturally it is the REITs that will receive most of the blame as they have a fiduciary responsibility towards their investors to buy buildings at attractive prices, with good outlooks and with the potential for short-, mid- and longterm gains. Needless to say that REITs are only one type of buyer where this kind of risk persists and one cannot rule out that similar things may have happened in transactions where pension funds or insurance companies acquired large portfolios of properties.