Painful Soft Landing for China’s Housing Market

No matter the asset class, dramatic price booms are often followed by an even more dramatic price plunge that destroys the wealth of many. The bigger the boom the harder and more likely the crash, and soft landings are few and far between.

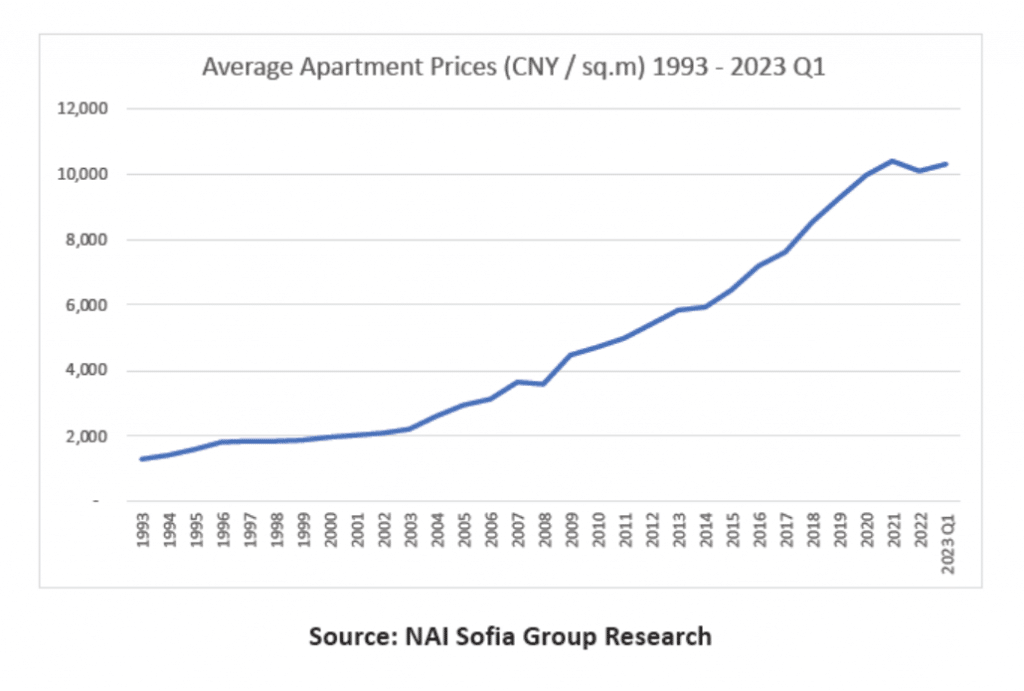

So it’s worth noting that one of the largest and longest booms in real estate history seems to have beaten the odds and entered a soft landing. China’s housing prices over the past few years have been largely flat.

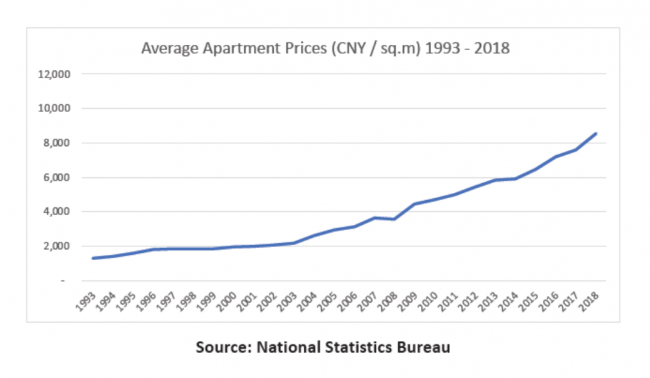

An epic boom

For sure, if this is a soft landing, it hasn’t been snowflake soft. But the situation could have been orders of magnitude worse if home prices had actually plummeted as so often happens with giant asset bubbles.

Long-time observers of China’s real estate market will recall that as early as 15 years ago economists were crying alarm about the country’s home prices being far too high and warning that a crash was increasingly likely. Plenty of numbers seemed to support their case, as did the strange phenomenon of new apartment buildings long built but sitting completely empty, even newly built neighborhoods and whole towns with hardly a soul living in them.

But prices continue to rise, and while speculation certainly contributed to their ascent, real-world fundamentals were also propping up demand. These fundamentals included China’s unprecedented rate of urbanization, increasing wages, strong GDP growth and rising prosperity overall.

The engineered ending

It was a golden era for developers, who could easily turn even underfunded or mismanaged projects into success stories by simply waiting for square meter prices to rise enough for their project to become profitable – ‘real estate is a forgiving asset class’, as the old saying goes. And banks were often willing to finance new projects based largely, it seems, on this very calculus.

But as the average cost of a home climbed above 15, 20, even 30 times average annual income in various cities (for comparison, the US median home prices typically ranges from 5-7 times annual income.), and with the looming possibility of a disastrous price plunge, China’s government decided enough was enough.

Market economics and government measures were already starting to flatten out price growth, and in mid-2020 the government moved to end the cycle of risky financing by introducing its Three Red Lines policy. This effectively made it impossible for many developers to obtain financing, preventing them from starting new projects and sometimes even finishing projects already begun.

Introduction of the Three Red Lines shook the entire real estate industry chain to its roots, pushing many developers towards bankruptcy, preventing them from paying off creditors and suppliers, and rendering some too short on cash to complete construction on pre-purchased homes.

Current state of things

It has to be applauded when governments react wisely and manage to cool down a sector before it overheats and eventually crashes. And judging by recent data (amount of transactions carried out, per square meter prices of real estate in various cities, financial figures of banks that are financing real estate and property developers themselves) it seems that China has managed to navigate an immensely complex and important transformation of this industry quite well.

At this point China’s government has pretty much abandoned the Three Red Lines and has also made sure that there is liquidity in the real estate industry so that projects are being completed and individual homebuyers are receiving their apartments, office units and even retail spaces. But there are still open questions about market health, especially in tier 3 and tier 4 cities where only with further urbanization all newly built apartments will be able to be absorbed by the market.

From a whole-economy perspective, it remains to be seen what will replace housing’s contribution to GDP growth. Until recently the real estate and construction industries and related services were believed to account for 25% to 30% of China’s GDP. A similarly pressing question is what will replace land sales as an income source for local governments. Such sales have declined drastically.

Somewhat insulated from the woes in residential real estate, commercial real estate in China – including offices, factories, warehouses, hotels, shopping malls and more – is doing well, with generally high occupancies, stable or growing rates and continued strong international and domestic investor sentiment.